Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

→ Article explaining DINOv3 and demonstrating how to create similarity maps using cosine similarity formula.

Just look around. You probably see a door, window, bookcase, wall, or something like that. Divide these scenes into parts as small squares, and think about these squares. Some of them are nearly identical (different parts of the same wall), some of them are very similar to each other (vertically placed books in a bookshelf), and some of them are completely different things. We determine similarity by comparing the visual representation of specific parts. The same thing applies to DINOv3 as well:

With DINOv3, we can extract feature representations from patches using Vision Transformers, and then calculate similarity values between these patches.

DINOv3 is a self-supervised learning model, meaning that no annotated data is needed for training. There are millions of images, and training is done without human supervision.

In a high level, you can think of it like self-supervised learning models generate their own annotations.

DINOv3 uses a student-teacher model to learn about feature representations. There are two different models (student and teacher), and both models work on the same image but with different augmentations applied. The student model tries to generate the same feature output as the teacher model.

Yannic Kilcher has a video about DINO in general, you can watch it from here, or you can read the official paper of DINOv3 for in-depth information.

Vision Transformers divide image into patches, and extract features from these patches. Vision Transformers learn both associations between patches and local features for each patch. For example, let’s consider four yellow patches in the below image. They have similar appearance, because they all are the hoofs of this white horse. The Vision Transformer model learns these associations between patches, therefore these patches have similar patch embeddings. You can think of these patches as close to each other in embedding space.

I have an article about how to train an image classification model with Vision Transformers, you can read it for more information about ViTs.

After Vision Transformers generates patch embeddings, we can calculate similarity scores between patches. Idea is simple, we will choose one target patch, and between this target patch and all the other patches, we will calculate similarity scores using Cosine Similarity formula.

If two patch embeddings are close to each other in embedding space, their similarity score will be higher. I will show you how to implement Cosine Similarity formula in Python, but now lets talk about formula.

Wikipedia explains it very well: cosine similarity is a measure of similarity between two non-zero vectors defined in an inner product space. Cosine similarity is the cosine of the angle between the vectors; that is, it is the dot product of the vectors divided by the product of their lengths. It follows that the cosine similarity does not depend on the magnitudes of the vectors, but only on their angle.(wikipedia)

You can see the tire example from the above image, the angle between two vectors is close to zero because they have similar visual appearance. It is intuitive as well, as we know cos(0) is equal to 1, and cos(90) is equal to 0. Therefore, as the angle between two vectors is smaller, the similarity score is higher.

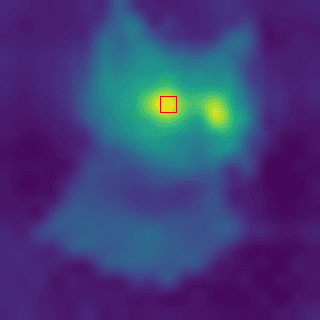

The idea is simple. First, we will generate patch embeddings from the image one by one. Next, we will choose one specific patch from the image and calculate similarity scores between that patch’s embedding and all the other patches’ embeddings. In the end, we will have similarity scores for each patch, and we will display them with colors.

You can follow the GitHub repository of DINOv3 for installation, and you need to have a GPU-supported PyTorch environment.

Okay, now we can start coding.

import torch

import torchvision.transforms as T

import numpy as np

import cv2

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

2. Pretrained Vision Transformer Model

First, you need to download a pretrained model, you can find the models on the GitHub page. First, you need to accept some agreement that META prepared. Then you can download pretrained models. I downloaded dinov3_vits16_pretrain_lvd1689m-08c60483.pth model. Dont forget to change DINOV3_LOCATION, CHECKPOINT_PATH, and MODEL_NAME.

# DINOv3 setup

DINOV3_LOCATION = "/home/omer/vision-ws/dinow3-ws/dinov3"

CHECKPOINT_PATH = "/home/omer/vision-ws/dinow3-ws/dinov3_vits16_pretrain_lvd1689m-08c60483.pth"

MODEL_NAME = "dinov3_vits16"

model = torch.hub.load(

repo_or_dir=DINOV3_LOCATION,

model=MODEL_NAME,

source="local",

weights=CHECKPOINT_PATH,

)

model.eval().cuda();

3. Read and Process Image

We need to resize the image, because it has to be divisible by 16. Our patch size is 16x16, therefore I resized the image to 320×320. You can choose any size you want, but it has to be divisible by 16.

# Load and resize to exact multiple of 16

img_path = "cat.jpg"

orig_bgr = cv2.imread(img_path)

img = cv2.cvtColor(orig_bgr, cv2.COLOR_BGR2RGB)

# Use 320x320 which is exactly 20x20 patches of 16x16

RESIZE = 320

PATCH_SIZE = 16

img_resized = cv2.resize(img, (RESIZE, RESIZE), interpolation=cv2.INTER_AREA)

plt.imshow(img_resized);

# Preprocess for DINOv3

transform = T.Compose([

T.ToPILImage(),

T.ToTensor(),

T.Normalize((0.485, 0.456, 0.406), (0.229, 0.224, 0.225))

])

# add batch dimension and apply transforms

inp = transform(img_resized).unsqueeze(0).cuda()

print(f"Input shape: {inp.shape}")

Output is: Input shape: torch.Size([1, 3, 320, 320])

4. Extract Patch Embeddings

# Extract patch embeddings (features)

with torch.no_grad():

features = model.forward_features(inp)

features = features['x_norm_patchtokens'][0].cpu().numpy() # 'x_norm_patchtokens': contains normalized features for each patch token.

print("size of the features:", features.shape)

Output is: size of the features: (400, 384)

Output makes sense, our patches are 16×16, and the image size is 320×320. So, we have 20 patches vertically (320/16), and 20 patches horizontally, resulting in 400 (20×20) patches in total. And for each patch, we have a patch embedding that is a 384-dimensional vector. This 384 depends on the ViT model.

5. Display image with patches and calculate similarity scores

Okay, this is the last part. As I said before, we will choose one patch from the image, and then calculate similarity scores with every other patch. I explained all the important parts with comment lines, but the idea is simple, we just calculate similarity scores using the cosine similarity formula, and then display the result with colors.

# Check actual number of patches

num_patches = features.shape[0]

grid_size = int(np.sqrt(num_patches))

# Calculate actual patch size on display

actual_patch_size = RESIZE // grid_size

# Draw EXACT patch grid

grid_img = img_resized.copy()

for i in range(1, grid_size):

x = i * actual_patch_size

cv2.line(grid_img, (x, 0), (x, RESIZE), (255, 0, 0), 2)

for j in range(1, grid_size):

y = j * actual_patch_size

cv2.line(grid_img, (0, y), (RESIZE, y), (255, 0, 0), 2)

# Click handler

def on_click(event, x, y, flags, param):

if event != cv2.EVENT_LBUTTONDOWN:

return

# Calculate which patch was clicked

patch_x = min(x // actual_patch_size, grid_size - 1)

patch_y = min(y // actual_patch_size, grid_size - 1)

idx = patch_y * grid_size + patch_x

print(f"Clicked patch ({patch_y}, {patch_x}), index: {idx}")

# Get reference feature

# feats --> 400,384

referance_feature = features[idx] # 1,384

"""

Compute cosine similarity with all patches

divide dot product by product of norms(l2) to normalize

@ --> dot product

np.linalg.norm --> l2 norm

"""

print(features.shape) # 400,384

print(referance_feature.shape) # 384,1

similarities = features @ referance_feature / (np.linalg.norm(features, axis=1) * np.linalg.norm(referance_feature) + 1e-8) # 400,1

similarities = similarities.reshape(grid_size, grid_size) # 20,20

# Resize similarity map to match image size

sim_resized = cv2.resize(similarities, (RESIZE, RESIZE), interpolation=cv2.INTER_CUBIC)

sim_norm = cv2.normalize(sim_resized, None, 0, 255, cv2.NORM_MINMAX)

sim_color = cv2.applyColorMap(sim_norm.astype(np.uint8), cv2.COLORMAP_VIRIDIS)

# Mark the clicked patch with a rectangle

marked_img = sim_color.copy()

top_left = (patch_x * actual_patch_size, patch_y * actual_patch_size)

bottom_right = ((patch_x + 1) * actual_patch_size, (patch_y + 1) * actual_patch_size)

# draw point to target patch

center = ((top_left[0] + bottom_right[0]) // 2, (top_left[1] + bottom_right[1]) // 2)

cv2.circle(marked_img, center, radius=5, color=(0, 0, 255), thickness=-1)

cv2.imshow("Cosine Similarity Map", marked_img)

# Display

cv2.namedWindow("DINOv3 Patches (click one)", cv2.WINDOW_NORMAL)

cv2.setMouseCallback("DINOv3 Patches (click one)", on_click)

cv2.imshow("DINOv3 Patches (click one)", grid_img)

cv2.waitKey(0)

cv2.destroyAllWindows()

Okay, that’s it from be, but not from DINO 🙂 I had an article about Grounding DINO as well, you can read it: