Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

→ An article explaining Grounding DINO and how to detect objects with text prompts.

I have so many articles about closed-set object detection, and most of them are similar to each other, create a GPU-supported environment, prepare a dataset, then train an object detection model such as YOLO, Faster R-CNN, or DETR. These models are great, but there are multiple steps, and depending on your dataset and computing power, the whole process take a decent amount of time. Using Grounding DINO, you can skip all the steps that I mentioned for detecting objects.

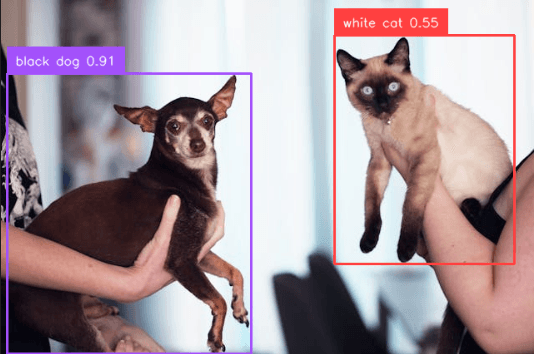

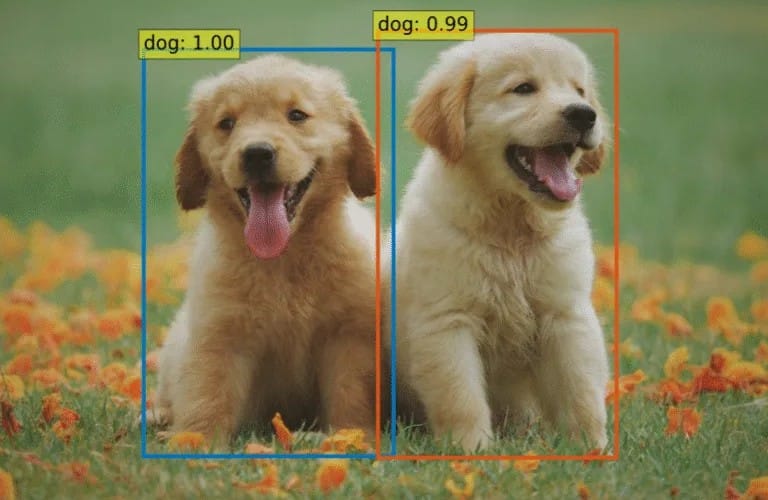

Grounding DINO is an open-vocabulary object detector, meaning that it is not restricted to predefined labels like in closed-set object detectors. It expects text input, and it can be any sentence like “red car in the left lane“, “cute baby“, or “apples“. If your text input is relevant to the image, there will be bounding box coordinates with a confidence value just like in closed-set detectors.

In this article, I will give you an introduction to Grounding DINO, set up the environment, and show you how to detect objects with text input. Before starting to talk about Grounding DINO, there are few concepts that you must know.

Also, I have a YouTube video about this article, you can watch it.

Actually, most of the models you see on the internet are closed-set object detectors. You have predefined labels like “car”, “person”, “plane”, and the model can only detect these. If you have a big and clean dataset, these models are great. The pipeline is the same for different models; create a GPU-supported environment, prepare a dataset, then train an object detection model.

Model detects objects from known classes (predefined labels in the training set), and it can also detect objects from unknown classes. It labels unknown objects as “unknown”. This helps to avoid classifying unknown objects as known objects. There are few models for open-set object detection, and to be honest, I have never used these models.

Model can detect objects from any text input, but of course, text inputs must be relevant. But there are no boundaries, the text input can be anything from a sentence to a word like “football player sitting on the side of the bus”, “green apples”, or directly “apple”. Grounding DINO is a great example of this category.

Okay, now we can start talking about Grounding DINO.

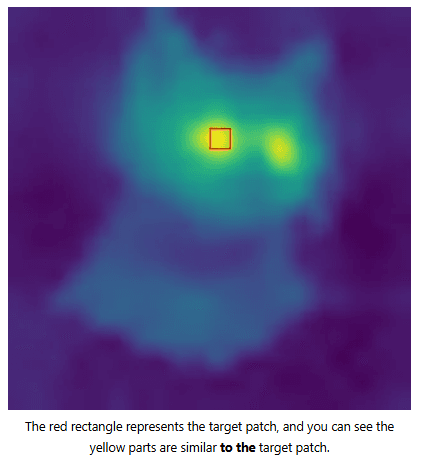

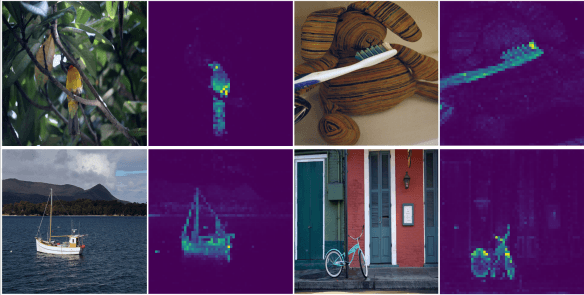

DINO is a self-supervised learning method to train Vision Transformers (ViT). Self-supervised training is done without any human supervision, with no annotated data. The model learns directly from images, and produces a feature map.

There are two different models: a teacher and a student model. There is one image input, and an augmented version of this input is fed to the student and teacher models. The student model gets both local and global views, and the teacher model gets global views. The student model aims to generate output as close as possible to the teacher model’s output. This way the model learns and updates weights. Actually, the student model is updated so that its output is closer to the teacher model’s output, and then the teacher model is updated using EMA (exponential moving average) of the student model.

Grounding DINO uses DINO for feature extraction, and now we can start to talk about Grounding DINO.

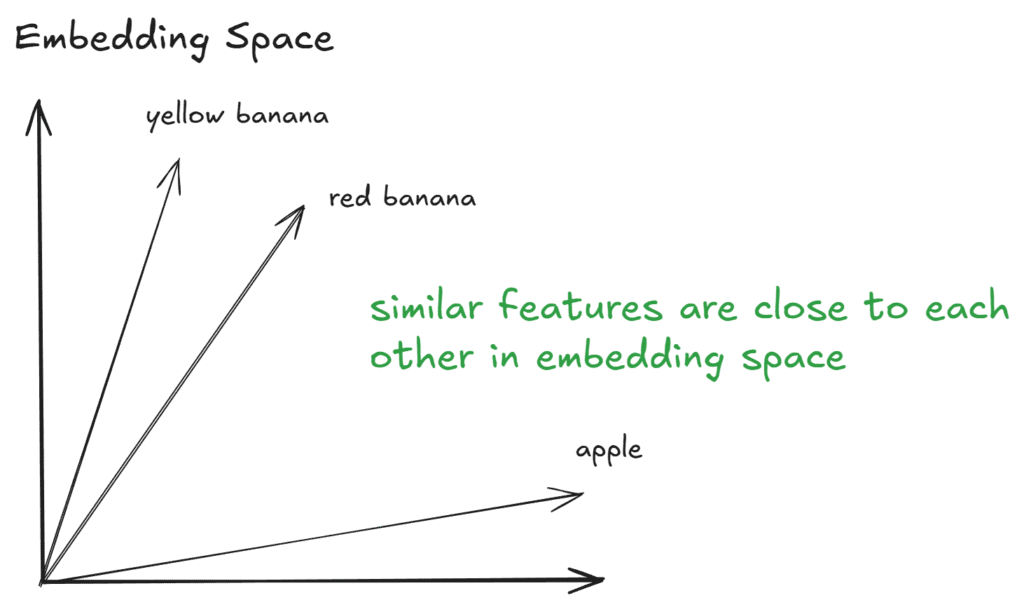

At a high level, DINO extracts features from images and generates a feature map. It is called the image encoder. Grounding DINO uses a DINO-pretrained Vision Transformer (ViT-B/ViT-L) for feature extraction. There is one text encoder (BERT), and it encodes text input as embedding tokens. These tokens represent the meaning of the text input in the embedding space. Similar text inputs are close to each other in the embedding space.

Grounding DINO combines these image and text features via cross attention. The cross attention mechanism helps to learn about image and text associations (aligning text tokens with image features).

After the model fuses image features and text embeddings, it is time for prediction. Grounding DINO uses a Language-Guided Query Selection module to pick the most relevant features and feeds them into a modified DETR head for object detection.

If you want to learn more about DETR, I have a whole article dedicated to DETR. It includes how to train the model, make inference, and an explanation of DETR.

That was a brief introduction to Grounding DINO, and now it is time to detect objects with Grounding DINO.

I followed the official documentation for installation, and for both Windows and Ubuntu, I managed to create the environments.

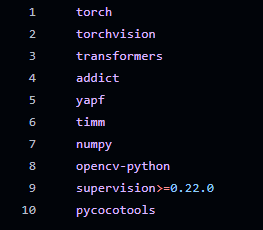

You can see the necessary libraries from above, and if you want to run models faster, you should create a GPU-supported PyTorch environment, then install other libraries. I already have a step-by-step guide for creating a GPU-supported PyTorch environment; you can read it.

First, clone the Grounding DINO repository:

git clone https://github.com/IDEA-Research/GroundingDINO.git

Install the required dependencies:

cd GroundingDINO/

pip install -e .

Download pre-trained model weights:

mkdir weights

cd weights

wget -q https://github.com/IDEA-Research/GroundingDINO/releases/download/v0.1.0-alpha/groundingdino_swint_ogc.pth

cd ..

If you decide to create a GPU-supported environment, you might get an error such as “NameError: name ‘_C’ is not defined“. No problem, you need to set the environment variable CUDA_HOME like below, and install libraries again with pip install -e

export CUDA_HOME=/path/to/cuda-12.9

Okay, now we can start to detect objects with Grounding DINO. I created a new Jupyter notebook inside the GroundingDINO folder that we cloned. First, we need to import the necessary libraries.

import cv2

from PIL import Image

import numpy as np

from torchvision.ops import box_convert

from groundingdino.models import build_model

from groundingdino.util.slconfig import SLConfig

from groundingdino.util.utils import clean_state_dict

from groundingdino.util.inference import annotate, load_image, predict

import groundingdino.datasets.transforms as T

from huggingface_hub import hf_hub_download

Lets check if the environment is GPU-supported:

import torch

print(torch.cuda.is_available()) # Output must be True

Now download and load the model. You can directly download the model from the internet as well, but I prefer to download it from the code:

def load_model_hf(repo_id, filename, ckpt_config_filename, device='cpu'):

cache_config_file = hf_hub_download(repo_id=repo_id, filename=ckpt_config_filename)

args = SLConfig.fromfile(cache_config_file)

model = build_model(args)

args.device = device

cache_file = hf_hub_download(repo_id=repo_id, filename=filename)

checkpoint = torch.load(cache_file, map_location='cpu')

log = model.load_state_dict(clean_state_dict(checkpoint['model']), strict=False)

print("Model loaded from {} \n => {}".format(cache_file, log))

_ = model.eval()

return model

# Grounding DINO model

ckpt_repo_id = "ShilongLiu/GroundingDINO"

ckpt_filenmae = "groundingdino_swint_ogc.pth"

ckpt_config_filename = "GroundingDINO_SwinT_OGC.cfg.py"

model = load_model_hf(ckpt_repo_id, ckpt_filenmae, ckpt_config_filename)

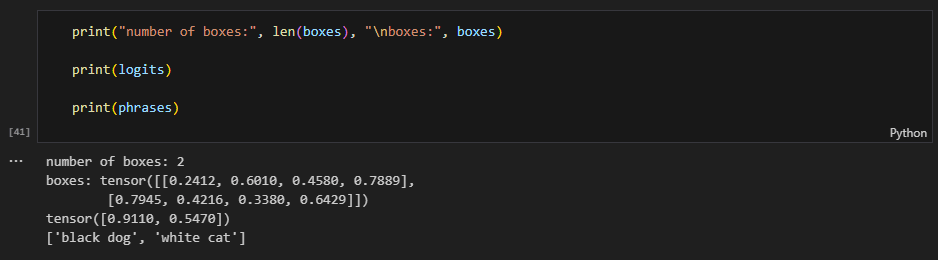

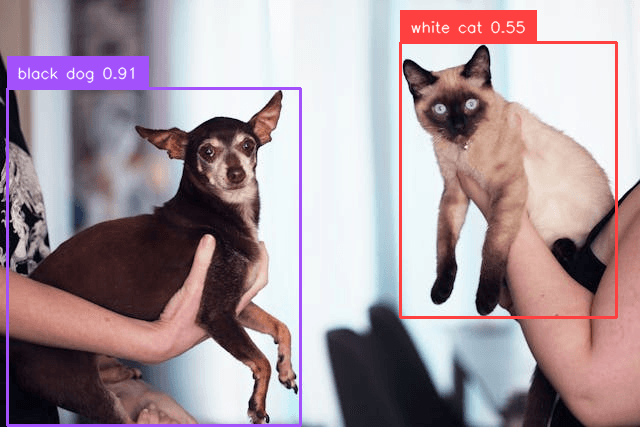

Now, lets test the model on an image. You can give as many prompts as you want at once:

# multiple text input

TEXT_PROMPT = "black dog . white cat ."

BOX_TRESHOLD = 0.45

TEXT_TRESHOLD = 0.25

# path to the image

local_image_path = "test_image.jpg"

# load the image

image_source, image = load_image(local_image_path)

# perform detection with text input on image

boxes, logits, phrases = predict(

model=model,

image=image,

caption=TEXT_PROMPT,

box_threshold=BOX_TRESHOLD,

text_threshold=TEXT_TRESHOLD

)

# draw bboxes and label information

annotated_frame = annotate(image_source=image_source, boxes=boxes, logits=logits, phrases=phrases)

annotated_frame = annotated_frame[...,::-1] # BGR to RGB

You access output via the boxes, logits, and phrases variables.

Image.fromarray(annotated_frame)

Okay, that’s it from me. I hope you liked it, and if you have any questions, feel free to ask me (siromermer@gmail.com)